Symbolism

in the 1934 Drawing

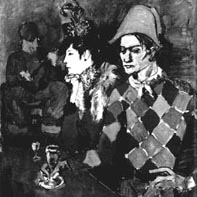

Picasso's Harlequin

Picasso's best known alter

ego is the Harlequin, a mysterious character with classical origins who has long

been associated with the god Mercury and with Alchemy and the Underworld. Harlequin's

traditional capacities to become invisible and to travel to any part of the world

and to take on other forms were said to have been gifts bestowed on him by Mercury.

It was also said that the secrets of Alchemy were to be found concealed within

the Harlequinade.

Harlequin is also a established character of Punch

and Judy theatre who in his local forms of 'Christoforo' and 'Pulchinelli', was

a popular feature of Barcelona street life at the turn of century.

Picasso undoubtedly

saw many such performances at this time, he even assisted in some of Pére

Romeu's puppet shows at Els Quatre Ghats and he would have also seen re-enactments

of Harlequin's triumph over Death in Barcelona's annual street carnivals.

Wine

was one of Harlequin's traditional accoutrements which he often used to seduce

women, occasionally Picasso's Harlequin appears to do the same thing as is alluded

to in his famous painting 'Au Lapin Agile', 1905.

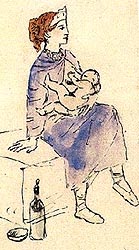

Picasso's harlequin

also appears as the father of an infant or yearning for paternity, this is strongly

associated with the traditional Harlequin and his ability to breast feed his own

children which in turn is an allusion to his status as an androgyne.

Picasso

also symbolically links Harlequin's wine with pregnancy as alluded to in the 1905

drawing 'Circus Artist and Child,'depicting a mother breast feeding her child

with a wine bottle at her feet which has been adapted with a teat to become a

baby's feeding bottle.

In the Three

Dancers and the 1934 drawing there is a further and quite astonishing cryptic

interlinking of this wine and pregnancy symbolism.

Picasso

also concealed a number of Harlequins in his most famous painting Guernica. These

hidden Harlequins appear to be magically undermining the forces of death in the

painting, which is reminiscent of Harlequin's traditional triumph over Death in

the Barcelona carnival.

tOP

Oedipus

According

to numerous Picasso biographies, when Picasso was about thirteen years old, his

father, a passionate amateur painter, gave him his paintbrushes and ceased painting

altogether. This appears to have taken on great psychological significance later

in Picasso's life for he equated it with patricide, a killing of his father's

creativity. The paintbrush was to become an important symbol that Picasso identified

with his own creative powers and masculinity.

Picasso recognised the

symbolic connection between this event in his early life and the Oedipus complex

of Sigmund Freud. He then adopted Oedipus as a secretive alter ego because the

story provided a wealth of symbolic associations that Picasso already identified

with in his art.

Oedipus

had been a popular theme amongst the Surrealists and others around Picasso in

the 1920's. Picasso appears to have embraced the theme at around that time, this

is apparent in a drawing he made on the subject in 1926.

In

Sophocles' play, Oedipus is exposed as a baby boy by his father, the king of Thebes.

The king did this to prevent the unfolding of a prophecy that he would die at

the hands of his son. Oedipus' feet were pieced by a piece of wood and he was

hung in a tree and left to die, but was rescued and bought up by shepherds. Picasso

already identified with Crucifixion and so the Crucifixion aspect of the story

reinforced his identification with Oedipus. Picasso's identification with Oedipus

was strengthened still further because as soon as Oedipus realises that he has

unwittingly killed his father and married his mother, he blinds himself and goes

into self imposed exile. Blindness was an important theme for Picasso, he once

stated that painting was a 'blind man's profession'. Themes of blindness emerged

early in his pictures and recurred many times. Associated with soothsaying and

prophecy, blindness had personal connotations for Picasso, for he was believed

by some of his close friends to have had the power of prophecy.

Exile was another

feature of Picasso's life that provided a symbolic link with Oedipus. From 1904

onwards, Picasso lived the life of an exile for his art. He was also a member

of the Spanish colony of Paris, many of whose members were political exiles because

of their membership of the Anarchist movement with which Picasso was also closely

linked. Then after 1936, Picasso swore not to return to Spain whilst Franco was

in power. Oedipus, despite losing his prince's

birthright eventually becomes

a king. Picasso also identified with kings, we see this in his famous signature

, 'Yo el Rey', and in a 1906 sculpted head where of harlequin as king. Christ,

the king of the Jews, was another of Picasso's alter egos. Kingship was therefore

an important feature in Picasso's choice of alter egos.

There

is a further link between Oedipus in Picasso's 1941 play, 'Desire Caught by the

Tail,' in which an artist called 'Big Foot' takes one of the leading roles. 'Big

Foot' has been closely identified with Picasso by art historians; his name appears

to have been derived from the name of Oedipus which means 'Swollen Feet,' in its

original Greek.

tOP

Wagner and Picasso

At the

turn of the century in Barcelona a number of poets and artists, including Picasso,

formed a literary group called Valhalla. Although the group's activities remain

to this day something of a mystery, it seems from the name Valhalla, that Wagner

and his operatic storytelling may have been one of their main interests.

Wagner had been very popular throughout Europe and was at this time making

an important impact on the cultural scene in Barcelona. His operas revived Norse

and Arthurian legends with underlying mystical themes that an inspiration to the

Symbolists and Modernistas with whom Picasso was associated.

Picasso's

interest in Wagner has not gone unreported; he almost certainly attended some

of the Wagner operas that were performed at his favourite haunt, Els Quatre Ghats.

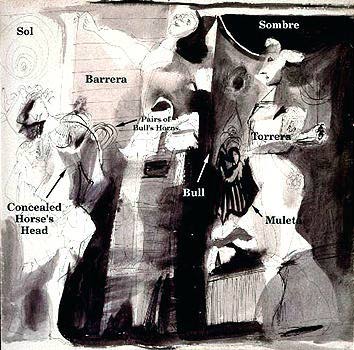

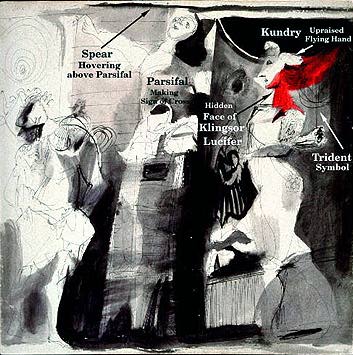

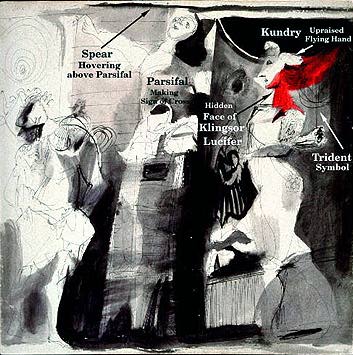

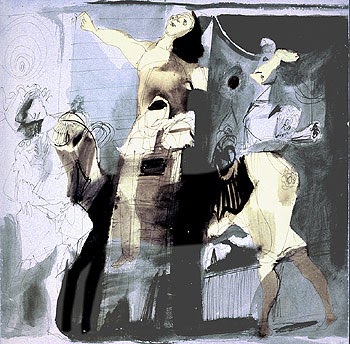

The 1934 drawing

contains an important Wagnerian theme that appears to be unique in Picasso's work.

It depicts what is probably the most dramatic scene in 'Parsifal' - the moment

when the spear that once killed Christ hovers over Parsifal's head after being

hurled at him by the evil magician Klingsor.

This

passage in the opera had special symbolic significance for Picasso in 1934 because

it related closely to his personal life at that time and also to his concern about

the rise of Hitler and the threat of a second world war.

tOP

Hitler and The Spear of Destiny

Both Guernica and the 1934 drawing conceal references to a mystical battle between

Picasso and Hitler in connection with the Spear of Destiny. This hidden pictorial

narrative, set in the context of Wagner's opera Parsifal, reveals some uncanny

associations with events in Hitler's life and with his quest to dominate Europe.

Vienna 1909-1913

According to the account of Dr Walter Stein, the young Hitler whilst living

as a down and out in Vienna undertook a penetrating study of the Occult meanings

underlying Wolfram Von Eschenbach's Thirteenth Century Grail Romance, 'Parsival'.

Stein through various contacts with Hitler became convinced that he was deeply

involved with the Occult and had an experienced spiritual mentor, possibly linked

to the infamous 'Blood Lodge of Guido Von Liszt.

Hitler

later claimed in Mein Kampf, that these had been the most vital years of his life

in which he learned all he needed to know to lead the Nazi Party.

Stein

got to know Hitler because of their mutual interest in the Spear of Destiny -

a relic on display in the Hapsburg's treasury at the Hofmuseum in Vienna.

The

relic was said to have phenomenal talismanic power having once been used at the

Crucifixion to wound the side of Christ. According to legend, possession of the

Spear would bring its owner the power to conquer the world, but losing it would

bring immediate death. The relic had been owned by a succession of powerful European

rulers down through the centuries and eventually came to be in the possession

of the Hapsberg Dynasty.

Hitler

confided to Stein that the first time he saw the Spear he had witnessed extraordinary

visions of his own destiny unfolding before him.

In

1923, on his deathbed, Hitler's mentor Dietrich Eckart, a dedicated Satanist and

central figure in the Occult Thule Society and a founder member of the Nazi party,

said:

'Follow

Hitler ! He will dance, but it is I who have called the tune !'

'I have

initiated him into the 'Secret Doctrine', opened his centres in vision and given

him the means to communicate with the Powers.'

'Do

not mourn for me: I shall have influenced history more than any other German.'

On

12th March 1938, the day Hitler annexed Austria, he arrived in Vienna a conquering

hero. He first port of call was to the Hofmuseum where he took possession of the

Spear which he immediately sent to Nuremberg, the spiritual capital of Nazi Germany.

At 2.10 on 30th

April, 1945, during the final days of the war, after considerable bombing of Nuremberg,

the Spear fell into the hands of the American 7th Army under General Patton. Later

that day, in fulfilment of the legend, Hitler committed suicide.

tOP

Parsifal

Wagner's

opera Parsifal features prominently in the 1934 drawing, it was originally based

on Wolfram Von Eschenbach's thirteenth century Grail romance, Parsival.

Picasso knew Wagner's version of the story and identified himself with Parsifal.

In the 1934 drawing, at the age of 52, he reveals, albeit secretly, the extent

of this symbolic identification.

It

has been well reported that the letters of Picasso's name had magical significance

for him. The first four, Pica, means spear in Spanish; which would certainly be

one reason why Picasso might identify with Parsifal in Wagner's opera. Picasso

would have realised a further significant link in the final stages of the opera.

In the second act, Parsifal begins to suffer the pain of Christ's wound in the

process of a mystical identification with Christ. By 1934, Picasso had long identified

himself with Christ and the Crucifixion in his art and the wound was already one

of his personal symbols for suffering and yearning for its resolve.

The

Spear that had once wounded the side of Christ is pivotal in Wagner's story. Klingsor,

a powerful black magician steals it and with it wounds Amfortas, the King of the

Guardians of The Holy Grail. He then flees with the Spear to his castle where

he dominates the surrounding area using powerful black magic. All this while,

Amfortas is destined to lay in agony from the wound which never heals; his only

hope of recovery being the Spear's return.

Parsifal,

an heroic fool, is prophesied to return the Spear and heal Amfortas. In an effort

to prevent the prophecy coming true, Klingsor uses magic to lure the hero to his

Castle where his men are hiding in ambush. Parsifal overcomes Klingsor's men but

suddenly Klingsor appears on the castle ramparts and in a final attempt at the

hero's destruction, he utters the following words:

Halt,

I have the right weapon to to fell you ! The fool

shall fall to me through

his master's Spear.

Klingsor hurls the Spear, but as if stopped by

the hand of God, it hovers motionless above Parsifal's head. Parsifal reaches

up and grasps the Spear and with it makes the Sign of the Cross, saying these

words:

With

this sign I rout your enchantment,

As the Spear closes the wound which you

dealt him with it

may it crush your lying splendour,

into mourning and

ruin.

Klingsor and his Castle then sink into the sea as if hit by

an earthquake, and the gardens that once surrounded the castle turn into a wasteland.

Parsifal restores the Spear and heals Amfortas of his wound. He then

becomes anointed as the new King of the Guardians of The Holy Grail.

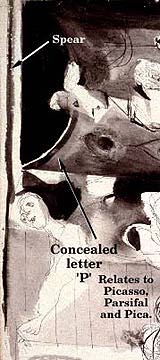

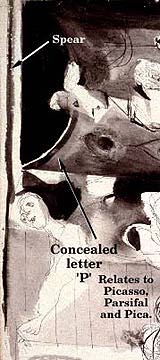

In

the 1934 drawing this pivotal scene is portrayed by the spear hovering above Picasso's

head. The spear runs along the top edge of the drawing and when the image is rotated

90 degrees to the left it forms the shaft of a huge letter 'P" in conjunction

with the black semi-circle in the upper right corner. The 'P' denotes a cryptic

Picasso signature and refers to the artist's identifications with 'Pica' and Parsifal.

The

central figure is identifiable with Parsifal reaching up and making the Sign of

the Cross.

His

'flying hand' concealed within the island of light in the right hand figure's

face can be seen to be blocking Klingsor's advance, it is located immediately

to the left of Klingsor's face which in turn seems to descend from the rear end

of the spear in the upper right corner.

The figure on

the right would seem to characterise Kundry, the witch who was present at Christ's

Crucifixion and who under Klingsor's spell attempts to seduce Parsifal. In the

drawing she appears possessed by Lucifer or the Devil, both of whom are appropriate

characterisations of Klingsor.

Behind

the hidden face there is a trident form, which seems to reinforce the hidden face's

connection with Lucifer.

According

to Dr Walter Stein and others, Hitler was convinced that in the ninth century

he had been incarnated as the historical Klingsor, sometimes known as Landulf

II of Capua !

Stein

had been a acquaintance of Hitler in the years preceding World War One and claimed

that Hitler had at that time undertaken a penetrating study of Von Eschenbach's

story and fathomed it's deepest occult meanings.

The

self identification of Picasso with Parsifal and the self-identification of Hitler

with Klingsor appears by some uncanny means to have found its way into the 1934

drawing which might indicate that Picasso had access to secretive information

about Hitler and his occult activities at least five years before the Second World

War.

tOP

Frankenstein

In 1931,

Universal Studios released the movie Frankenstein, in which the monster

as most of us recognise him today

made his first appearance. The 1934 drawing

appears to contain an inverted double portrait of Frankenstein's monster

derived from this movie.

Picasso,

who was often described as a monster, loved the cinema and probably saw the 1931

'Frankenstein' soon after its release in France. It appears clear from the drawing

that he went on to identify a number of symbolic associations between himself

and the monster and identified other symbolic associations between the monster

and Hitler's Aryan Superman.

Frankenstein's

monster, like Oedipus and Picasso, were all in a sense responsible for the destruction

of their fathers*. All three also suffered a form of blindness; Picasso symbolically,

Oedipus by self infliction and Frankenstein's monster because at first his eyes

were too sensitive to light.

All

three also underwent a form of crucifixion; Picasso symbolically, Oedipus when

he is exposed by his father, the monster when he is created as well as when he

dies under the sign of a burning cross. Finally, all three also experienced a

form of exile; Picasso at the turn of the century in Paris and again in the 1930's

as a protest against Franco, Oedipus by his own edict and the monster by being

violently ostracised from the day of his creation.

The Hanged Man

symbol with which Picasso closely associated also features in the movie when parts

of a dead body are stolen from a gallows to be used for the creation of the monster.

A further association

involves the monster's huge feet which Picasso would have related to the 'Swollen

Feet' of his alter ego Oedipus and later with the artist 'Big Foot' in his play

'Desire Caught by the Tail.'

The

only real human contact the monster makes is with a little girl called Maria who

picks some flowers and offers one to the monster. The flower girl is another important

Picasso theme. In the movie, after the monster inadvertent kills her, the flower

girl makes an important reappearance in the guise of Dr Frankenstein's bride holding

a wedding bouquet.

The concealed,

inverted portrait of the monster in the 1934 drawing appears to have its right

eye hanging out, which is a detail that seems to link him symbolically with Odin

who had to pull out one of his eyes and hang inverted from a tree. The monster's

one good eye, by association, can be seen as a reference to the third eye.

In

regard to the 1934 drawing's concentration of Germanic themes, it would seem that

the Frankenstein image is linked with the theme of Hitler and the Third Reich.

According to

Rauschning Hitler often talked about the Aryan Superman having a Cyclops eye.

'Some men

can already activate their pineal glands to give a limited vision into the secrets

of time...but the new type of man will be equipped for such vision in the same

manner as we now see with our physical eyes', Hitler said.

He also

believed that the Supermen would be in our midst in a short time. They would have

superhuman strength and powers and nothing would be hidden from their vision and

no power on Earth would prevail against them. 'They would be the Sons of the Gods,'

he said.

Picasso

would have certainly known about Neitzsche's Superman from whom Hitler's concept

of the 'new man' was partially derived, he also appears to have known it was Hitler's

intention to create such a monster who in the drawing he relates to Frankenstein's

monster because he is a similar type of man made man, a criminal who is more dead

than alive, a creature of hell and destruction. This association seems to be all

the more appropriate because hidden within the face

of the monster in the

drawing, there appears to be an amorphous portrait of Hitler.

The

drawing also contains other apparent references to the Third Reich, an SS symbol,

a concentration of related Germanic and occult themes and perhaps the suggestion

in the drawing that the dominant force (Nazi Germany) on the right is making a

brutal attack on the helpless victim (Europe) on the left.

The

1934 drawing contains an astonishing interrelationship of themes pertaining to

Picasso, Christ, Hitler, Odin, Oedipus, Frankenstein's monster and to the flower

girls who feature in a number of early Picasso pictures and significantly, also

in Wagner's opera Parsifal.

*

The death of Dr Frankenstein is alluded to but left somewhat ambiguous at the

end of the movie, presumably in order to have a happy ending.

tOP

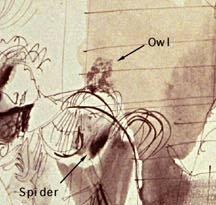

A Hidden Picasso Bestiary

Picasso

loved animals and they often made an appearance in his work. In 1937, he began

illustrating a special limited edition of Buffon's celebrated 'Histoire naturelle,'

for his dealer Ambroise Vollard. The book included 31 etchings of animals, birds

and insects.

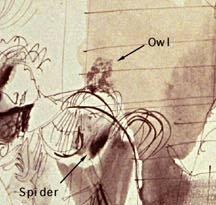

Similarly, 1934 drawing contains many animal forms, including:

bulls, fishes,

owls,

a

horse, a spider,

a snail,

a

wolf, an exotic bird and a sphinx-like dog.

All

these animal forms are cleverly concealed and appear to relate to the drawing's

central theme of death.

tOP

Alchemical

Contexts

Alchemical

Images

The Symbolists

and the Surrealists, with whom Picasso's art was intimately associated, sourced

a great many of their ideas from Alchemy and Magic. Picasso's art was likewise

indebted to this mystical tradition.

The 1934 drawing is replete with alchemical symbolism and was made for a

specific purpose at the zenith of the artist's creative life. Because of this

and the fact that Picasso's symbols tend to be universal, the drawing appears

to contain a message that seems to challenge our materialist attitude towards

the world and which has the ability to plunge us into the magical living world

of symbols.

Alchemy

is associated with a variety of dispersed belief systems, some of which are thousands

of years old. The Tao, the Mithraic cult, the Isis cult, Gnosticism, the Kabbala,

Astrology and the Tarot are a few of its sources of occult wisdom. Some of the

pagan religions of Europe were much influenced by the Eastern mystical cults that

the Romans had popularised throughout their Empire. With the rise of the Christianity,

such religions were purged from everyday life and became heresies that could only

be practiced in secrecy. At the time of the Crusades between the 11th and 14th

centuries, Europeans made contact with the culture and mysticism of the East and

bought back to Europe a wealth of Eastern occult understanding which was to have

a further influence on the pagan and other traditions at the bedrock of Western

alchemy.

Alchemy

is concerned with the transformation of the individual into an enlightened being,

hence the well known metaphor of turning base metal into gold. It uses a language

of symbols and laws many of which were known in the ancient world. It's practice

involves an initiation from where the initiate passes stages of understanding

and development toward the ultimate goal, which is sometimes symbolised by a star.

The drawing seems

to be an alchemical treatise that serves on the one hand to clarify the nature

of man's dilemma in a dualistic and seemingly chaotic world and on the other,

poetically express all the forces and concerns acting on the artist's life at

the time.

tOP

Mirror

Images

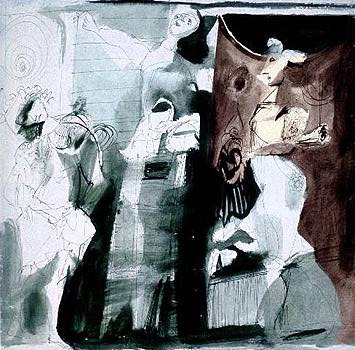

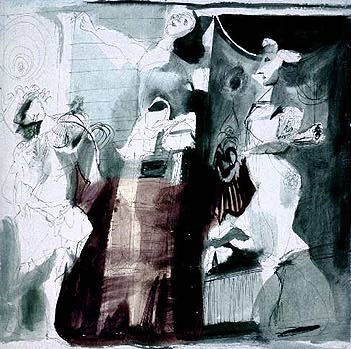

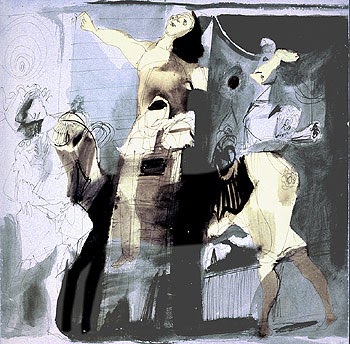

The 1934 drawing

contains two extraordinary mirror images that can be seen by placing a mirror

vertically down the centre of the composition. The right hand side reveals a bull-like

horned demon flanked by two guardians

and

the left hand side reveals a terrifying apocalyptic crucifixion.

The use of willow wands,

wax dolls, water divining and magic mirrors are well known features of Tao magic

which happens to be closely related to European sorcery. Taoist magical practices

were bought to Europe centuries ago by Arabs trading with China. Taoist magicians

would often possess a magical mirror which he would use to compel his demon to

appear to him in his true shape, once this was accomplished the magician would

be freed from the demon's power.

This

freeing from the demon's power appears to have been Picasso's magical intention

in incorporating such images into the drawing. It is especially relevant in the

context of Picasso's own overpowering feelings of crucifixion and melancholy in

1934 and to his vision of the European apocalypse that was to be bought about

by Hitler.

The

images are shown in negative for added impact.

tOP

Melencolia

In

the year 1514 the German painter and engraver Albrect Dürer made his most

famous engraving, 'Melencolia'.

The engraving is an allegory describing

the creative melancholy of the artist and is thought to be a symbolic self portrait.

Dürer's Melencolia is replete with alchemical symbolism related directly

to much of the symbolism in the 1934 drawing.

Picasso

was a great admirer of Dürer and owned at least one original print by the

artist, given to him by Max Jacob; he also owned a an expensive German edition

of reproductions of Dürer's work.

Dürer's

theme of Saturnalian Melancholy appears to have been derived from a treatise by

a German physician named Heinrich von Nettesham, written around 1510, and entitled

'De occulta philosophia.'

Since

classical times artistic Melencolia was thought of as a depressed state of mind

that takes away an artist's enthusiasm for his work. It's cure was believed by

Renaissance astrologer's to be aided by the charm of a magic square and in particular

the Jupiter magic square which appears in the upper right hand corner of Dürer's

engraving. The square is magic because each row, each column and each diagonal,

add up to the same number, which in the Jupiter magic square is 34. The numerals

3 and 4 also denote special importance in Alchemy because they represent the spiritual

transformation of the alchemist. 3 symbolises the limited, finite life of the

physical world and everyday existence and 4 symbolises the infinite realm of the

spirit and the cosmos. Their product is 12, the number of Tarot card the Hanged

Man, which in turn symbolises the union of physical life and spiritual life.

The

number 34 is relevant to the drawing because it refers the year it was made and

to its predominant theme of Crucifixion because of its association to the symbolism

of the Hanged Man in the Tarot.

In

Melencolia, Dürer has incorporated the engraving's date, 1514, into the lower

row of numbers in the magic square.

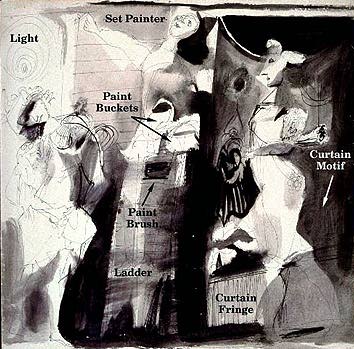

In a similar

way Picasso hid the date of production into the 1934 drawing. The digits '34'

appear in many places within the black ink of the composition, but are only made

visible after computer enhancement.

The

square format of the drawing is rare in Picasso's work, and in this case, it appears

to signify that the drawing is itself a magic square, intended to charm off the

melancholy that was beginning to affect Picasso's life at the time.

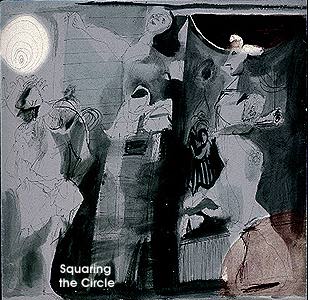

The 1934 drawing contains a number of other esoteric elements which appear to

have been borrowed from Dürer's Melencolia. In both compositions for example,

there is a concealed squaring of a circle. In the lower left corner of Dürer's

work there is a circle in the form of a globe, in the upper left corner there

is a semi-circle in the form of a rainbow, and in the upper right there is a quarter

circle defined by a bell rope and in the lower right corner the circle disappears

altogether, thereby breaking the sequence. This is a circle being halved systematically

through three corners of the frame of the composition and finally disappearing.

In the 1934 drawing, we find the same process taking place. In the upper left

corner, there is a circle in the form of the spiral motif, in the upper right

corner, there is a semi circle in the form of a black half moon, and in the lower

right corner, there is a quarter circle painted in wash, finally in the lower

left corner all traces of the circle disappear, again breaking the sequence. The

symbolism indicates liberation or transcendence from melancholy and it is also

strongly indicative of

death and resurrection.

The

two pictures also contain very similar iconography, in each there is a dog, a

ladder, two angels, the tools of the artist's trade: paints and a brush in the

Picasso and woodworking tools in the Dürer. All this leaves little doubt

that Dürer's greatest engraving was an important source in the creation of

the 1934 drawing.

tOP

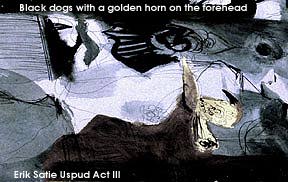

Erik

Satie

Along

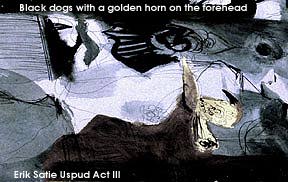

the right hand edge of the drawing there is a concealed image of a dog like creature

associated with Anubis, one of the Egyptian gods of the underworld.

This

sTRANGE animal form also appears to be strongly connected with Erik Satie's 1892

ballet 'Uspud'. Satie was a Rosicrucian and had been a great friend of Picasso,

who was said by Picasso, to have been one of the most important influences in

his life. The two had worked together on Jean Cocteau's 'Parade' in 1917, and

they had a strong mutual interest in Alchemy and the Occult.

Uspud

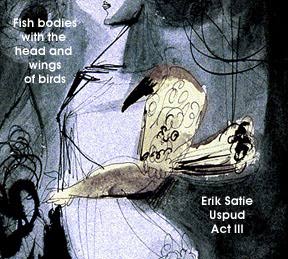

is a deeply mystical and satirical work; it is short and full of strange imagery,

like the 1934 drawing, it unfolds around the theme of the Crucifixion. In the

final act, there is a description that strongly resembles the image of Anubis

in the drawing. There is a further description of fishes with the heads and wings

of a bird which appears to be represented pictorially in the same part of the

drawing.

Uspud Act III

The top of a mountain:

a crucifix above.

Uspud,

clad in homespun garments. prostrates himself before the crucifix: for a long

time he prays and weeps.

When

he raises his head, Christ unfastens his right arm from the cross, blesses Uspud

and disappears. The holy spirit penetrates Uspud.

Procession

of male and female saints: saint Cleopheme spits his teeth into his hand: saint

Micanar bears his eves on a platter the blessed Marcomir has his legs burnt to

a cinder: saint Iduciomare's body is pierced with arrows, saint Chassebaigre,

confessor, in violet robes: saint Lumore with a sword; saint Gebu with redhot

irons; saint Glunde with a wheel: saint Krenou with a sheep; saint Japuis, with

doves escaping from a cleft in his forehead: saint Umbeuse spinning wool: the

blessed Melou the lame: saint Vequin the flayed: saint Purine the unshod: saint

Plan, preaching friar: saint Lenu with a hatchet. Their voices summon Uspud to

martyrdom. He is penetrated by an unquenchable thirst for suffering. He tears

off his homespun robes and appears clad in the white tunic of neophytes. He prays

again. A swarm of demons rise up on all sides. They assume monstrous forms: black

dogs with a golden horn on the forehead; fish bodies with the head and wings of

birds: giants with bulls heads. snorting fire through their nostrils. Uspud commends

his soul to the lord, then gives himself up to the demons who tear him to pieces

in a fury. The Christian church appears radiant with light and escorted by two

angels bearing palm leaves and crowns. She takes Uspud's soul in her arms and

raises him up towards Christ, who is resplendent in heaven. End.

Apart

from the two similarities in imagery with that in the 1934 drawing, Picasso seems

to have used Uspud as a source for a series of 1959 crucifixion sketches related

to the bullfight. They depict Christ crucified in a bullring, detaching his right

arm from the cross, just as described in act III.

tOP

Isis

The

female figure on the right of the drawing appears to represent Isis wearing her

traditional moon headdress and in the company of the god Anubis her jackel headed

companion.

Isis represents

different aspects of the feminine archetype, in ancient Egypt, she was the mother

goddess and the queen of the underworld. In Egyptian art she was often depicted

in the presence of her underworld companion Anubis, who conveyed the souls of

the dead for judgment.

In

the Roman Empire, the cult of Isis was very popular throughout the Mediterranean

area. It focused on the celebration of the mysteries of the death and the resurrection

of Osiris. Isis, had been the consort of Osiris, and after his murder she recovered

the scattered parts of his body and restored them to life. Osiris then became

king of the dead and his son Horus became king of the living. The story of Isis,

Osiris and Horus parallels the Christian mysteries of the virgin birth

and

the resurrection. It is also the origin of certain the Christian symbol of the

Madonna and Child.

The cult of Isis

continued to be practised throughout the former Roman Empire right up to the sixth

century AD when it was finally driven underground by Christianity. Isis lived

on within certain esoteric traditions throughout the middle ages and continues

to be an important part of the Alchemical tradition, which is almost certainly

why she is represented in the 1934 drawing.

tOP

The Mithraic Cult

Picasso's

use of the bullfight theme appears to have an association with the Mithraic cult.

The American art historian Ruth Kaufman identified the use of Mithraic iconography

in Picasso's Crucifixion of 1930 and associated it with the writings of Georges

Bataille who was Picasso's friend at that time.

Picasso also seems to

have referred to the Mithraic cult in his work before 1930. In 1901, he made a

series of studies and paintings of women at the infirmary of Saint Lazare, in

which the subjects are often wearing a Mithraic cap, a kind of bonnet traditionally

worn by Mithras and associated with alchemy. The patients at Saint Lazare wore

a similar type of headgear; Picasso's exaggerated rendition of it has been linked

to the Phrygian cap - the Mithraic cap by another name,

which later became

a symbol of the French revolution.

The Mithraic

cult was early Christianity's most serious rival as it spread from Syria, Anatolia

and Phrygia throughout the Roman Empire. Its origins are obscure but it was known

to have been one of the religions of ancient Indo-Persia. The earliest record

of the cult dates as far back as 1400 B.C. The cult was a form of sun worship

involving astrology. Its was symbolically represented by the god Mithras and the

eternal struggle between good and evil. It was an exclusive male cult with seven

grades of initiation, symbolized by a seven runged ladder which was believed to

lead to immortality. Most important in the stages of initiation was the slaying

of the bull, a re-enactment of Mithras' killing of the cosmic bull of creation,

symbolising the conquest of evil and death. The Mithraic cap represented freedom

from materialism and another of its symbols, the Tau cross, signified the uniting

of opposites. The cult was introduced to the West in the 1st century AD by the

Romans and it became very popular among the military and the merchant classes.

By the 4th century, it became the target of Christian persecution and gradually

died out, but its legacy continued to live on in the more secretive practices

of Alchemy. Symbolic facets of the legacy also found their way into Christianity,

Mithras' birth was celebrated on the 25th of December, and cakes marked with a

cross, representing the Earth, were traditionally eaten at the cult meal.

The

1934 drawing is full of Mithraic symbolism derived from the traditions of alchemy

and the artists knowledge of ancient culture and symbolism. The theme of the bullfight

is partly a Mithraic theme. Picasso's use of the seven runged ladder and the Tau

cross in the drawing appear to be derived from the same source, as are a number

of other more obsure symbols. The symbolism of Mithraism was extensive and parts

of it correspond astonishingly with other esoteric disciplines including the Kabbala

and the Tarot.

tOP

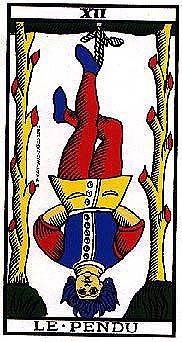

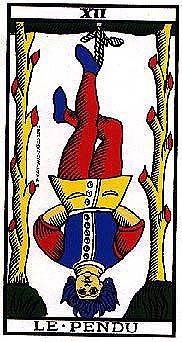

The Hanged Man

Picasso

was very conversant with the Tarot and seems to have identified closely with the

card known as the Hanged Man. It depicts a man with his hands tied behind his

back hanging by one of his feet from a gibbet placed between two trees.

Though interpretations

of the card vary it is generally believed to symbolise a self-sacrifice in which

the subject undergoes an important transformation from a materialistic consciousness

to a spiritual consciousness.

The

Hanged Man is in a state of solitude and submission to divine will, he hangs suspended

between the forces of heaven and earth and his sacrifice brings him mystical knowledge

and redemption.

The

card corresponds astrologically with the sign of Scorpio, Picasso's birth sign,

and its number is 12 which is related to inspiration and personal development.

The central figure

in Picasso's Three Dancers features the outstretched arms of a traditional Crucifixion

in combination with the crossed legs of the Hanged Man.

In

the 1934 drawing, whose composition is heavily derived from The Three Dancers,

the central figure has one leg raised above the other upon the steps of a ladder.

If imagined from

the side, the figure's legs would have the same crossed appearance as the legs

of the Hanged Man and those of the central figure in The Three Dancers.

This

reveals a cryptic identification between the Hanged Man and the central figure

in the 1934 drawing, who in turn is identifiable with Picasso.

The

origin of the Hanged Man is said to be connected with the sacrifice of Odin, the

chief of the Norse gods, who according to mythology, hung upside down in a tree

for nine days to gain entry to the underworld and learn the meaning of the runes.

As a precondition to his self sacrifice Odin was wounded with his own spear and

had to pull out one of his eyes.

Picasso

would have doubtless identified with the Odinic sacrifice and realised its obvious

symbolic connections with Christ's crucifixion and with the 'crucified' exposure

and self inflicted blindness of Oedipus.

Odin

according to myth, finally meets his end in a terrible apocalypse in which the

universe is destroyed. The theme of the Odinic apocalypse, called Ragnorok, would

have been well known to Picasso, not only because of his insatiable appetite for

legends and myths, but also because it featured in the final act of Gotterdammerung,

the Twilight of the Gods, the final part of Wagner's famous most famous operatic

work, The Ring Cycle. In Wagner's version of the story, it

is Odin who brings

about Ragnorok because of his pride. Wagner signifies Ragnorok by the breaking

of Odin's spear, the symbol of his power which equates symbolically with the spear

in Parsifal and also with Picasso's name.

Another

important symbolic association between Odin and Picasso is that Odin's counterpart

in the Southern pantheon is the god Hermes or Mercury. Picasso had been closely

identified with Hermes from an early date, his friend Guillaume Apollinaire, openly

referred to him as the Harlequin Trimegistus, a derived name of Hermes Trimegistus,

Hermes the Thrice Great, the god of Alchemy.

tOP

Interpretations

of the 1934 Drawing

This

section contains a number of scholars' interpretations of Picasso's work and the

1934 drawing.

Jung's

1932 Article on Picasso

"As

a psychiatrist, I almost feel like apologising to the reader for becoming involved

in the excitement over Picasso. Had it not been suggested to me from an authoritative

quarter, I should probably never have taken up my pen on the subject. It is not

that this painter and his strange art seem to me too slight a theme - I have,

after all, seriously concerned myself with his literary brother, James Joyce.

On the contrary, his problem has my undivided interest, only it appears too wide,

too difficult, and too involved for me to hope that I could come anywhere near

to covering it fully in a short article. If I venture to voice an opinion on the

subject at all, it is with the express reservation that I have nothing to say

on the question of Picasso's 'art' but only on its psychology. I shall therefore

leave the aesthetic problem to the art critics, and shall restrict myself to the

psychology underlying this kind of artistic creativeness.

For almost twenty

years, I have occupied myself with the psychology of the pictorial representation

of psychic processes, and I am therefore in a position to look at Picasso's pictures

from a professional point of view. On the basis of my experience, I can assure

the reader that Picasso's psychic problems, so far as they find expression in

his work, are strictly analogous to those of my patients. Unfortunately, I cannot

offer proof on this point, as the comparative material is known only to a few

specialists. My further observations will therefore appear unsupported, and require

the reader's good will and imagination.

Non-objective

art draws its contents essentially from 'inside.' This 'inside' cannot correspond

to consciousness, since consciousness contains images of objects as they are generally

seen, and whose appearance must therefore necessarily conform to general expectations.

Picasso's object, however, appears different from what is generally expected -

so different that it no longer seems to refer to any object of outer experience

at all. Taken chronologically, his works show a growing tendency to withdraw from

the empirical objects, and an increase in those elements which do not correspond

to any outer experience but come from an 'inside' situated behind consciousness

- or at least behind that consciousness which, like a universal organ of perception

set over and above the five senses, is orientated towards the outer world. Behind

consciousness there lies not the absolute void but the unconscious psyche, which

affects consciousness from behind and from inside, just as much as the outer world

affects it from in front and from outside. Hence those pictorial elements which

do not correspond to any 'outside' must originate from 'inside.'

As

this 'inside' is invisible and cannot be imagined, even though it can affect consciousness

in the most pronounced manner, I induce those of my patients who suffer mainly

from the effects of this 'inside' to set them down in pictorial form as best they

can. The aim of this method of expression is to make the unconscious contents

accessible and so bring them closer to the patient's understanding. The therapeutic

effect of this is to prevent a dangerous splitting-off of the unconscious processes

from consciousness. In contrast to objective or 'conscious' representations, all

pictorial representations of processes and effects in the psychic background are

symbolic. They point, in a rough and approximate way, to a meaning that for the

time being is unknown. It is, accordingly, altogether impossible to determine

anything with any degree of certainty in a single, isolated instance. One only

has the feeling of strangeness and of a confusing, incomprehensible jumble. One

does not know what is actually meant or what is being represented. The possibility

of understanding comes only from a comparative study of many such pictures. Because

of their lack of artistic imagination, the pictures of patients are generally

clearer and simpler, and therefore easier to understand, than those of modern

artists.

Among

patients, two groups may be distinguished: the neurotics and the schizophrenics.

The first group produces pictures of a synthetic character, with a pervasive and

unified feeling. When they are completely abstract, and therefore lacking the

element of feeling, they are at least definitely symmetrical or convey an unmistakable

meaning. The second group, on the other hand, produces pictures which immediately

reveal their alienation from feeling. At any rate they communicate no unified,

harmonious feeling-tone but, rather, contradictory feelings or even a complete

lack of feeling. From a purely formal point of view, the main characteristic is

one of fragmentation, which expresses itself in the so called 'lines of fracture'

- that is, a series of psychic 'faults' (in the geological sense) which run right

through the picture. The picture leaves one cold, or disturbs one by its paradoxical,

unfeeling, and grotesque unconcern for the beholder. This is the group to which

Picasso belongs*.

In

spite of the obvious differences between the two groups, their productions have

one thing in common: their symbolic content. In both cases the meaning is an implied

one, but the neurotic searches for the meaning and for the feeling that corresponds

to it, and takes pains to communicate it to the beholder. The schizophrenic hardly

ever shows any such inclination; rather, it seems as though he were the victim

or this meaning. It is as though he had been overwhelmed and swallowed up by it,

and had been dissolved into all those elements which the neurotic at least tries

to master. What I said about Joyce holds good for schizophrenic forms of expression

too: nothing comes to meet the beholder, everything turns away from him; even

an occasional touch of beauty seems only like an inexcusable delay in withdrawal.

It is the ugly, the sick, the grotesque, the incomprehensible, the banal that

are sought out - not for the purpose of expressing anything, but only in order

to obscure; an obscurity, however, which has nothing to conceal, but spreads like

a cold fog over desolate moors; the whole thing quite pointless, like a spectacle

that can do without a spectator.

With

the first group, one can divine what they are trying to express; with the second,

what they are unable to express. In both cases, the content is full of secret

meaning. A series of images of either kind, whether in drawn or written form,

begins as a rule w with the symbol of the Nekyia - the journey to Hades, the descent

into the unconscious, and the leave-taking from the upper world. What happens

afterwards, though it may still be expressed in the forms and figures of the day-world,

gives intimations of a hidden meaning and is therefore symbolic in character.

Thus Picasso starts with the still objective pictures of the Blue Period - the

blue of night, of moonlight and water, the Tuat-blue of the Egyptian underworld.

He dies, and his soul rides on horseback into the beyond. The day-life clings

to him, and a woman with a child steps up to him warningly. As the day is woman

to him, so is the night; psychologically speaking, they are the light and the

dark soul (anima). The dark one sits waiting, expecting him in the blue twilight,

and stirring up morbid presentiments. With the change of colour, we enter the

underworld. The world of objects is deathstruck, as the horrifying masterpiece

of the syphilitic, tubercular, adolescent prostitute makes plain. The motif of

the prostitute begins with the entry into the beyond, where he, as a departed

soul, encounters a number of others of his kind. When I say 'he,' I mean that

personality in Picasso which suffers the underworld fate - the man in him who

does not turn towards the day-world, but is fatefully drawn into the dark; who

follows not the accepted ideals of goodness and beauty, but the demoniacal attraction

of ugliness and evil. It is these antichristian and Luciferian forces that well

up in modern man and engender an all-pervading sense of doom, veiling the bright

world of day with the mists of Hades, infecting it with deadly decay, and finally,

like an earthquake, dissolving it into fragments, fractures, discarded remnants,

debris, shreds, and disorganised units. Picasso and his exhibition are a sign

of the times, just as much as the twenty-eight thousand people who came to look

at his pictures.

When

such a fate befalls a man who belongs to the neurotic, he usually encounters the

unconscious in the form of the 'Dark One,' a Kundry of horribly grotesque, primeval

ugliness or else of infernal beauty. In Faust's metamorphosis, Gretchen, Helen,

Mary, and the abstract 'Eternal Feminine' correspond to the four female figures

of the Gnostic underworld, Eve, Helen, Mary, and Sophia. And just as Faust is

embroiled in murderous happenings and reappears in changed form, so Picasso changes

shape and reappears in the underworld form of the tragic Harlequin - a motif that

runs through numerous paintings. It may be remarked in passing that Harlequin

is an ancient chthonic god.

The

descent into ancient times has been associated ever since Homer's day with the

Nekyia. Faust turns back to the crazy primitive world of the witches' sabbath

and to a chimerical vision of classical antiquity. Picasso conjures up crude,

earthy shapes, grotesque and primitive, and resurrects the soullessness of ancient

Pompeii in a cold, glittering light - even Giulio Romano could not have done worse!

Seldom or never have I had a patient who did not go back to neolithic art forms

or revel in evocations of Dionysian orgies. Harlequin wanders like Faust through

all these forms, though sometimes nothing betrays his presence but his wine, his

lute, or the bright lozenges of his jester's costume. And what does he learn on

his wild journey through man's millennial history? What quintessence will he distil

from this accumulation of rubbish and decay, from these half-born or aborted possibilities

of form and colour? What symbol will appear as the final cause and meaning of

all this. In view of the dazzling versatility of Picasso, one hardly dares to

hazard a guess, so for the present I l would rather speak of what I have found

in my patients' material. The Nekyia is no aimless and purely destructive fall

into the abyss, but a meaningful katabasis eis antron, a descent into the cave

of initiation and secret knowledge. The journey through the psychic history of

mankind has as its object the restoration of the whole man, by awakening the memories

in the blood. The descent to the Mothers enabled Faust to raise up the sinfully

whole human being - Paris united with Helen - that homo totus who was forgotten

when contemporary man lost himself in one-sidedness. It is he who at all times

of upheaval has caused the tremor of the upper world, and always will. This man

stands opposed to the man of the present, because he is the one who ever is as

he was, whereas the other is what he is only for the moment. With my patients,

accordingly, the katabasis and katalysis are followed by a recognition of the

bipolarity of human nature and of the necessity of conflicting pairs of opposites.

After the symbols of madness experienced during the period of disintegration there

follow images which represent the coming together of the opposites: light/dark,

above/below, white/black, male/female, etc. In Picasso's latest paintings, the

motif of the union of opposites is seen very clearly in their direct juxtaposition.

One painting (although traversed by numerous lines of fracture) even contains

the conjunction of the light and dark anima. The strident, uncompromising, even

brutal colours of the latest period reflect the tendency of the unconscious to

master the conflict by violence (colour = feeling). This state of things in the

psychic development of a patient is neither the end nor the goal. It represents

only a broadening of his outlook, which now embraces the whole of man's moral,

bestial, and spiritual nature without as yet shaping it into a living unity. Picasso's

drame interieur has developed up to this last point before the denouement. As

to the future Picasso, I would rather not try my hand at prophecy, for this inner

adventure is a hazardous affair and can lead at any moment to a standstill or

to a catastrophic bursting asunder of the conjoined opposites. Harlequin is a

tragically ambiguous figure, even though - as the initiated may discern - he already

bears on his costume the symbols of the next stage of development. He is indeed

the hero who must pass through the perils of Hades, but will he succeed? That

is a question I cannot answer. Harlequin gives me the creeps - he is too reminiscent

of that 'motley fellow, like a buffoon' in Zarathustra, who jumped over the unsuspecting

rope-dancer (another Pagliacci) and thereby brought about his death. Zarathustra

then spoke the words that were to prove so horrifyingly true of Nietzsche himself:

'Your soul will be dead even sooner than your body: fear nothing more l' Who the

buffoon is, is made plain as he cries out to the rope-dancer, his weaker alter

ego: 'To one better than yourself you bar the way' He is the greater personality

who bursts the shell, and this shell is sometimes - the brain."

*(Jung

added the following note in a 1934 version.)

"By

this I do not mean that anyone who belongs to these two groups suffers from either

neurosis or schizophrenia. Such a classification merely means that in the one

case a psychic disturbance will probably result in ordinary neurotic symptoms,

while in the other it will produce schizoid symptoms. In the case under discussion,

the designation 'schizophrenic' does not, therefore, signify a diagnosis of the

mental illness schizophrenia, but merely refers to a disposition or habitus on

the basis of which a serious psychological disturbance could produce schizophrenia.

Hence I regard neither Picasso nor Joyce as psychotics, but count them among a

large number of people whose habitus it is to react to a profound psychic disturbance

not with an ordinary psychoneurosis but with a schizoid syndrome. As the above

statement has given rise to some misunderstanding, I have considered it necessary

to add this psychiatric explanation."

tOP

Overview

of Thoughts on Picasso Drawing

by

Dr Ralph Goldstein

"Dated

12/5/34 15" square ink and gouache on paper then laid to card.

The pose and composition, are somewhat reminiscent of The Three Dancers, reproduced

by Penrose[9] on p.95. There the LHS figure (a shrieking maenad) has her head

tilted back even further than the LHS figure in this drawing. A similar crossing

/ crucifixion exists in both compositions. But the Dancers was Dionysian in character,

unlike this picture. Another immediately striking aspect of the picture is the

strong division into a light and a dark side by the use of the gouache. The RHS

figure is totally in the dark side.

On

the assumption that this picture is by Picasso then, surely, the LHS figure is

Marie-Therese Walther and the RHS figure is Olga Koklova, Picasso's then wife

(but formal divorce was imminent). She is not represented as sexual, but is forbidding)id(

and p posed (haughty dancer?). But perhaps there is a hint of the marital bed

in the lower background? And the stretched / crucified figure - psychologically,

not physically; there is no cross, more a Brechtian Chalk Circle - is Picasso

himself. His figure seems to stand on a ladder (a crucifixion symbol in earlier

paintings) with the left foot (RHS) vaguely outlined but on a higher step. Taking

account of the left knee and the right foot, it seems as if this figure may be

descending the ladder. Compare this compositional device with Minotauromachy,

in which an escaping bearded figure on the L.H.S looks back down from a ladder;

probably a symbol of Picasso himself.

On

the human level, it seems to be that the LHS figure does not wish to see, or has

been prevented / blind-folded, from seeing the problems caused by her (reciprocated)

love. And perhaps Picasso did blame her somewhat afterwards. In sharp contrast,

the gaze of the figure drawn against the dark background cannot be escaped.

But,

on a supra-personal level, Marie-Therese could also be the blind goddess of fate

- albeit she seems also to turn away in shame. What we seem to have is a (schizoid)

process of inflation - i.e. captured by archetypal powers - these human persons

/ figures having simultaneously to bear the Olympic burden of gods; of eternal

human questions or paradoxes.

I

am extremely grateful to Mark Harris both for letting me see this drawing and

for his generosity with his time and thoughts. The two women incarnate aspects

of the archetypal anima[5] and Picasso incarnates the Hermes/Eros life and death

principle, or struggle for the soul (psychopompus). But the humans are powerless

in the face of destiny - or the fates arranged by the gods. Picasso's anima, his

new creative inspiration/ arlir7lation is a kind of Faustian Helen; see p. 195

of M-L von Franz' paper [3].

The

immediate impact of the picture is on the observer's feelings, rather than aesthetic

senses - this is a picture drawn by someone in great pain and distress. How is

Picasso to be rescued from this crucifying fate? By Hermes guide of Souls and

source of the masculine aspects of life. If this struggle can be resolved Picasso

will be able to paint again; and, indeed, Hermes has already alighted on Marie-Therese's

shoulder (see below). The resolution is plain to see in the picture.

In

fact, Marie-Therese was an inspiration for many pictures. But this personal dark

night of the Soul occurred at a very dark (and darkening) period of history. Just

three years later Picasso was led to one of his greatest works, Guernica, 1937

[1]. Creative powers of such magnitude would not have been available while he

was stuck in the Dilemma represented in this picture of struggle and unhappiness.

We should note

that, as Jaffe (1988) wrote, "In the art of Picasso, the personal became

impersonal, his own experience became the experience of his age, of mankind''.

He also quotes Picasso as having said; "The work one does is another way

of keeping a diary". Thus, this psychological interpretation parallels the

art historical view.

Related

to the idea of a diary, to which this picture may well belong, is another sense

of the word hermetic. What is hermetic about this picture is that it prefigures

a decision about life involving others. Therefore, it is necessarily secret or

hi(hidden (as a diary usually is), until the decision can be announced. Additionally,

the decision is to some extent hidden or unannounced (unconscious) for the person

in the throes of such a conflict.

Details

We need to justify

the above view by reference to the details in the picture. Perhaps the key is

the light and the dark anima, a concept to which C.G. Jung refers in his comments

on the Picasso retrospective of 1932 in Zurich [4]. The anima and the animus are

two archetypal figures of especially great importance. They belong on the one

hand to individual consciousness and on the other hand they are rooted in the

collective UNCONSCIOUS, thus forming a bridge between the personal and the impersonal

(cultural, universal), the conscious and the unconscious [5]. One is feminine

and the other masculine (in terms of imagery and embodiment.) These figures often

appear early on in psychotherapy in terms of dreams, images and inter-personal

problems e.g. relationships, power and creativity.

So

the image of the 'dark night of the soul' (dark anima) can be applied to this

drawing. This is night in another sense, the night of the psychopomp (see [6]

p. 51), the night of generation and the night of dying. One relationship glows

as another fades with all the sense of loss and pain for the one who does the

leaving as well as the one who is left. Clearly, something has turned dark or

negative in the once fruitful wife. Her figure is placed against a very dark background.

Picasso is is also partly surrounded by dark background; he seems isolated. But

his right hand, outstretched, reaches into the light.

The

light anima is represented by the figure on the left who is drawn against a light

background and is very feminine and alluring. In fact, the girl / maenad is actively

masturbating), an (auto)erotic statement. Is she unaware of her own erotic power

and UNCONSCIOUS of the forces unleashed in others by her perceived eroticism?

The object perched

on the shoulder of Marie-Therese is a head(l and torso (cut off at the knees)

looking to the left. He is bearded with wings and a hat or helmet, and something

that seems to screen his vision, a screen matching the blindfold? There may be

7 lines in the lyre-like shape in front of his face. Some hold that the lyre invented

by Hermes had 7 strings (Graves p. 65). There is a picture of a terra cotta statuette

of a girl with Eros from the en(l of the classical period reproduced on p. 145

of Kerenyi's book on Eleusis [7]. The composition is startlingly similar, especially

in terms of Eros being perched on the shoulder of the girl.

However,

the Eros-like figure is bear(led and wears a cap reminiscent of Hermes' hat as

]illustrated on the cover of Kerenyi's book on Hermes Guide of Souls [6], taken

from an attic red-figured bowl. There Hermes carries his lyre in his left hand

and his magic wand in his right. He is also bearded.

Therefore,

it seems that this figure is a composite of Eros, son of Hermes and Hermes himself.

It is also probably an aspect Picasso himself.

On

the extreme RHS is a possibly a cartoon, reminiscent of the later Smoker series

in style, of Picasso's face worn on Olga's sleeve with a cut-off outstretched

something to the right (see studies for the Crucifixion [1929] reproduced in Blunt

[1] p. 27, plate lla). Now what is beyond the same arm towards the centre? A little

girl with her arms around what? A draped, almost swaddling, cloak heavily drawn

in? (See the later little girl with dove?) A reference to Madonna and child in

front of Olga? This may not be too fanciful if we remind ourselves of the Spanish

Catholic culture in which Picasso was brought up. The wife / Madonna and first-born

child are especially magical and profound symbolic beings.

Just

above these puzzling figures is a series of circular shapes within a dome, which

is almost connected to another puzzling shape)e, but strongly defined shape. There

is a dark circular disc surrounded by a lot of squiggly lines. Effort went into

this area of the drawing, yet the result is childish or corrupted. Is it conceivable

that it is a corruption of a nimbus, which is itself related to the idea of a

halo?

The nimbus,

or halo, surrounding the head of a holy person symbolises the divine light shining

from the sanctified personality; the MANDORLA, or vesica piscis, depicted here,

encloses the entire body of a person of special dignity and holiness [2].

A

person's wife and mother of the first-born child would have been such a special

person, until those feelings become corrupted or corroded by dread, antagonism

and divorce (splitting, separation). The possibilities of playing with the word

"pisces" may also be relevant. How should we read the strong light curve

under the very dark semi-circle above Olga's head? Perhaps there is an eclipse

of the moon (a fundamental symbol of the feminine) around (l Olga's head? Balanced

perhaps by the curious, almost child-like circles over Marie-Therese's head? But

these are not centred, but eccentric; not a true wholeness? See the idea of a

pearl oyster.

The

helmet shapes in the centre are empty of eyes. The figure which seems to have

all eye lla.s an ill-defined head! Indeed, one does not see him for quite a while.

There seem to be 4 heads where the body of the person stretched in both directions.

There is a thick dividing line down the middle (see Minotauromachy?) Are these

potential animus figures, fighters? Now the number 4 would be significant (fourfold

development; see M-L Von Franz)

Is

there a little monkey? or owl?), but faded, on top of the Hermes cap? Or just

a smudge?

Resolution

of the Dilemma

Picasso's trousered leg takes a step/l)points towards Marie-Therese

(they met in 1927). ,She cannot yet be pregnant with Maya (b. 5/10/35). Maya,

christened Maria Concepcion, which were the names of his 2 sisters and close to

Marie of Marie-Therese. But he called her Maya the mother of Hermes.

Between

the LHS figure and the centre figure - above and beyond the lines suggesting a

step-ladder - are strong horizontal lines, reminiscent of other drawings of Marie-Therese.

Here these lines may be a reference to the bario of the bull-fight. Once Picasso

comes out from behind the barrier / breaks cover and goes public with his desire

for a divorce and the freedom to be with Marie-Therese then he would be in as

much danger as if he were in the bullring. There was a great personal cost to

pay and Olga was threatening, under French divorce law, to take ownership of all

his work. Nevertheless, the drawing clearly prefigures Picasso's decision to go

ahead. It may be relevant that the date, signature and fingerprint are placed

below Picasso's right foot.

Bottom

centre right; are there doves / bird shapes between the leading leg of Olga and

the darkest part of the gouache?

Olga's

shoes; ballet dancer's shoe or is one foot winged as in Hermes figure? There is

something odd on Olga's head, possibly a bird. See an early bust of a Harlequin

from 1905 with a bird on top. See also African Art by Mauze p. 84 & p. 67;

a toucan (hornbill) presides over ploughing, sowing and harvesting (Baule from

Ivory Coast, ancestor mask topped with a toucan). So a reference perhaps to fecundity

and domesticity. Alternatively, or additionally, Mark Harris points out that this

may be Picasso's open left hand stretched across the light part of Olga's exquisitely

drawn face (especially the eye).

In

connection with the idea of representing both a personal and near universal problem

in art, it is worth quoting Neumann [8] p. 97 See also pp 93-94

The

need of his times works inside the artist without his wanting it, seeing it, or

understanding its true significance. In this sense he is close to the seer, the

prophet, the mystic. And it is precisely when he does not represent the existing

canon, but transforms and overturns it that his function rises to the level of

the sacral, for he then gives utterance to the authentic and direct revelation

of the numinosum.

There

is another group of crucifixion drawings made in 1932 at a time of stress - based

on study of Grunewald's Isenheim Altarpiece, a masterpiece of l6th cent expressionist

tragedy (p. 26)

We

know that Picasso was illustrating Ovid's Metamorphoses at this time, so he would

have been familiar with classical myths. Nevertheless, this probably does not

exhaust the contents of this drawing, especially the very dense working on the

body of the figure I take to be Picasso."

Dr Ralph Goldstein

is a clinical psychologist and Jungian Analyst who worked for a number of years

in close association with the late Dr Susan Bach of Switzerland.

References

[1] Anthony Blunt. Picasso's Guernica. Oxford University Press, 1969.

[2]

JC Cooper. An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols Thames and Hudson,

1979.

[3] C.G. Jung et al. Man and His Symbols. Picador, 1964.

[4] C.G.

Jung. The Spirit in Man, Art and Literature. ARK, 1966/1984.

[5] Emma Jung.

Animus and Anima. Spring publications, Texas, 1981.

[6] Karl Kereni. Hermes

Guide of Souls. Spring publications, Texas, 1997.

[7] Karl Kereni. Eleusis:

Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter. Princeton University Press, 1976.

[8] Erich Neumann. Art and the Creative Unconscious Routledge and Kegan Paul,

1959.

[9] Roland Penrose. Picasso. Phaidon Press, London, 1991.

tOP

An

Interpretation of the 1934 Drawing

by Eberhard

Fisch

The drawing, which was executed

spontaneously and 'off the cuff', provokes through the flow of its lines and the

dramatic clash of dark and light-coloured tones. The scene is made up of three

figures set in stark contrast to one another. On the left, a girl flirts with

her image in an oval-shaped mirror, held up by the rather indistinctly delineated

figure in mid-position. The mirror and the girl's head are at the same level,

and both are split up into black and white areas. A series of horizontal lines

emphasise the line of vision. The central figure has its arm fully extended and

its head thrown back, a posture that is perhaps intended to express effusive admiration

or a flattering attitude towards the young beauty. The figure in mid-position

is so unimportant that it cannot even be said whether a man or a woman is presented

here. The central motif is the oval-shaped mirror, and that is why it is positioned

in the visual centre of the drawing The young woman on the right, now past the

prime of her youth, and who makes a conspicuous pose when she strides into the

scene, is of greater significance. Both her body and her head with its distinctive

profile are bursting with energy, and suggest a certain aggressiveness. The dynamic

force set up by the numerous diagonals has a surprise effect. The chin is even

boldly underlined, the nose is exaggeratedly pointed. The woman's hair style is

quite unusual, bearing a resemblance to a pair of horns. However, it is not clear

what is to her immediate left and right. Is she holding something in her outstretched

hand (a black scarf?) and something else behind her back? Possibly, the artist

merely had objects in the background in mind. Some of the shapes around the figure

do actually suggest a bed, perhaps a four-poster, for in the top corner of the

picture the drapes of a curtain are just discernible. The latter descends from

the top edge of the picture in a sweeping curve, thus emphasising the woman's

head in a really peculiar fashion and, at the same time, forming a conspicuous

white line which appears to virtually grow out of her forehead. The heavy, black

semicircle above her head has its counterpart in the light-coloured, sun-like

spiral above the head of the younger woman. This striking phenomenon is undoubtedly

a key to a proper understanding of the drawing.

It is possible to construe

this drawing simply as a genre scene. The frolicsome young woman basks in her

beauty, her vanity being additionally emphasised by the figure in mid-position,

while the older woman observes the scene with a feeling of jealousy or suspicion.

The mass of black colour around her figure and her aggressive features build up

an extremely tense contrast to the left-hand area of the drawing, making the observer

sense that the playful scenario on the left is threatened by disaster looming

from the right.

But

the drawing can also be construed as an allegory transcending the elements that

simply model the real scene, and in which the characters take on a meaning in

the realm of ideas. The dramatic presentation of the figure approaching from the

right makes the assumption that this figure is a supernatural being quite a feasible

one. If the right-hand figure is viewed, for example, as a kind of angel of death

or as death itself (French: 'la mort'), what is illustrated here is then the old

vanitas theme. Whilst, on the left, beauty is still admiring her reflection in

the mirror, decay or death is already waiting in the wings, or even suddenly befalls

the young woman. The black semicircle above the mysterious figure on the right

can also be interpreted as an iconographical feature, as a 'black sun' (French:

'soleil noir'), in other words as a symbol for destruction. The 'black sun' topos

- that of the 'black mirror' and the 'black light' too - was often used by a close

friend of Picasso's, the poet Paul Eluard. In 'Guernica' too, Picasso's monumental

mural which was created three years later, there is a juxtaposition of light that

radiates and light that emits darkness.

The

figure on the right is an extremely unusual one - even in such a diverse oeuvre

as that of Picasso. It is highly probable that its precursors are to be found

in the late works of Johann Heinrich Fussli (1741-1825). Since 1932, ever since

his visit to the Kunsthaus in Zurich on the occasion of his retrospective exhibition

there, Picasso had often borrowed motifs and formal elements from Fussli's works.

The woman on the right in the drawing under discussion is sharply reminiscent

of the figures of dramatic and emotional women that appear in Fussli's works,

the features that call these to mind being the woman's clear-cut and distinctive

profile, her peculiar hairstyle, and the curve of the curtain 'joined', as it

were, to her head. Both the jealousy theme and that of 'a young woman threatened

by an older one' are frequently to be encountered in Fussli's works, and these

topics were, indeed, also of particular concern to Picasso in 1934. At the time,

Picasso's wife, Olga, was frantically jealous of his mistress, Marie-Therese Walter,

for whom he had even furnished a flat nearly opposite his own.

In

1950, Picasso took up the 'woman with mirror' motif once again. This time, a young

woman with a somewhat skeptical facial expression holds out to an older woman

a mirror in which the latter contemplates herself rather wistfully. The entire

area of the picture is strewn with sharp, prickly shapes suggestive of negative,

painful sensations. On the left, a vase of flowers is visible in the background.

There is no doubt that, far from being a mere fill-in, this motif actually has

an important symbolic function. Flowers in a vase are beautiful, but they soon

wilt. Once again, here we have the vanitas motif, linked to the short lifespan

of feminine beauty. But, in addition, this vase also calls to mind the rather

indefinite pictorial element to the left of the woman on the right in the drawing

of 1934. Perhaps it is a vase of flowers that is meant here, too.

Only

a few weeks before the creation of the newly-discovered drawing of 12.5.1934,

Picasso had already made a drawing in which the motif of a woman with an oval-shaped

mirror crops up. The woman sprawls around in front of a large mirror standing

on the floor, directly adjacent to which there is again a vase of flowers. In

the case of this drawing too, it would be difficult to deny that there is a symbolic

relationship between the flowers and the woman. Many of Picasso's pictures are

full of symbolism, and it is not at all unusual for small subordinate scenes to

have an inner connection with the main theme.

The

newly-discovered drawing of 12.5.1934 corresponds completely to Picasso's style

and intellectual stance at that period, and even epitomises the link, only recently

established and about which a report appeared in a Swiss art journal in 1992,

to Fussli's works. These motifs and compositional elements borrowed from Fussli

are themselves sufficient reason for me to rule out the possibility of the drawing

being a fake. Moreover, if that were the case, it would have had to be executed

by an artist of the same calibre as Picasso. And there is no such artist.

The

unusual action of an artist in concealing his signature and only leaving a fingerprint

to posterity can be explained by Picasso's private situation at the time. Perhaps

the drawing was a gift to a mistress, and Picasso preferred not to leave behind

any evidence that might have come to the notice of his extremely jealous wife.

At all events, the content of this drawing has a great deal to do with that eternal

topic: 'woman'.

tOP

In

Support Of The 1934 Drawing Being By Pablo Picasso

by Melvin Becraft

My study of Picasso's Unknown Masterpiece, a 1934 ink drawing titled by Mark Harris,

has resulted in 56 pages of addendum to the 1987 edition of my book, Picasso's

Guernica - Images within Images.

In 1981 I began finding hidden images

in Picasso's Guernica which led to the writing of my book. Ten years later Harris

began finding hidden images in the 1934 drawing and in 1993 wrote an essay on

the work which he sent to me in November 93. His essay noted similarities between

the 1934 drawing and several of Picasso's other works including Guernica of 1937